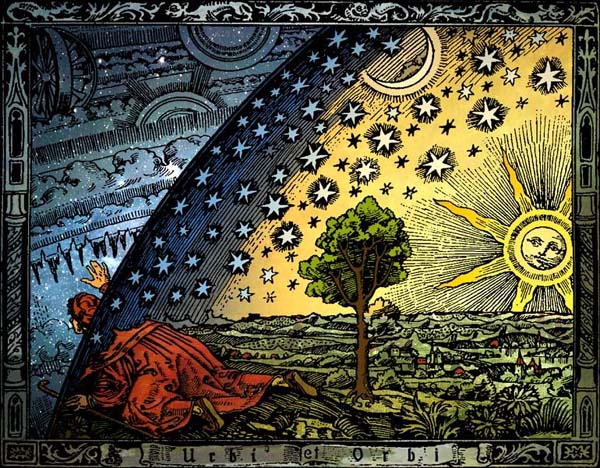

“The hero is the one who, while still alive, knows and represents the claims of the superconsciousness which throughout creation is more or less unconscious. The adventure of the hero represents the moments in his life when he achieved illumination–the nuclear moment when, while still alive, he found and opened the road to the light beyond the dark walls of our living death.” (Joseph Campbell The Hero with a Thousand Faces P. 259)

Although Joseph Campbell is a bit impermissively cavalier with his assertion that a hero attains illumination, or divine insight into his own deeds, one might more frugally admit that it is the hero that lives out an illuminated moment in time where the unconscious will or spirit of a people is embodied through some great deed of his. The hero therefore lives out some greater purpose–without as Campbell suggests–necessarily understanding it, though he undoubtedly senses that he is living in and through some great moment.

For example, when Odysseus killed the suitors in Ithaka upon returning home, he did so with both the assistance and direction of Athene. Now, does this give Odysseus some greater insight into the way of things, or “illumination”? No, it simply shows that he is a “favorite” or “chosen” person of Athene–because of his endurance and desire “always to seek after his own advantage”, and his ability “always to keep his head” in any difficult situation. And though he does gain insight and recognition of the “way of the world”, it would be a stretch to suggest that his action enlightens him or illuminates him about the nature of the gods. Therefore, Odysseus, as a hero who performs a culture defining action, does so by his own will and due to his virtuous attributes and the love of a goddess, but not because he is illuminated as to the will of the gods. What makes him a hero is that he brings about the potential for illumination for others through his deeds, not personal illumination for himself.

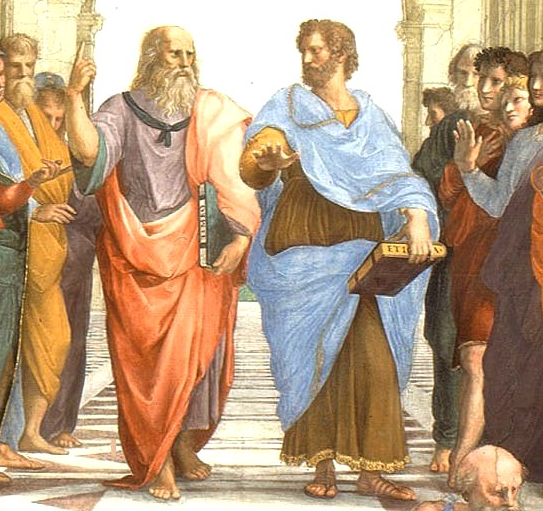

As we wrote yesterday, it is not simply the hero, but also the artist, author, or thinker who could bring forth an epoch-defining piece of work called “mythology”. Campbell, again, overstates the position of the author in this case:

“But if we are to grasp the full value of the materials, we must note that myths are not exactly comparable to dream. Their figures originate from the same sources–the unconscious wells of fantasy–and their grammar is the same, but they are not the spontaneous products of sleep. On the contrary, their patterns are consciously controlled(my italics). And their understood function is to serve as a powerful picture language for the communication of traditional wisdom. The trance-susceptible shaman and the initiated antelope-priest are not unsophisticated in the world nor unskilled in the principles of communication by analogy.” (Ibid P. 256)

This is a tricky spot for Campbell, for he is asserting that though a myth comes from the depths of the creative unconscious that its expression is consciously chosen and asserted by a discerning and potentially “illuminated” shaman or thinker. Given that Campbell’s source for notions of mythology coming from the unconscious was Carl Jung, the psychologist, let us see whether their words and thoughts on the source of mythology agree.

“A psychological reading of the dominant archetypal images reveals a continuous series of psychological transformations, depicting the autonomous life of archetypes behind the scenes of consciousness. This hypothesis has been worked out to clarify and make comprehensible our religious history.” (C.G. Jung, The Symbolic Life CW 18 Par. 1686, P. 742)

Though there is agreement on the fact that mythology as “dominant archetypal images” can enact transformations of a psychological and therefore cultural sort, there is not consensus on whether the author has conscious control of these changes. In fact, what is controlled may be the exact manner, wording, or expression of the action or artistic-object, but the content of the story, piece of art, or action are created first in the unconscious, not in the conscious mind of the actor or author. In fact, against Campbell’s theory, the artist or actor is far more the vessel or tool of the unconscious myth than he or she is the interpreter or greatest understander of it at all. For further information on the relationship between the artist and his work, particularly a work of mythological and cultural importance, let us turn to the psychologist and polemicist Friedrich Nietzsche:

“In a case like Wagner’s, which is in many ways an embarrassing one, although the example is typical, my opinion is that it’s certainly best to separate an artist far enough from his work, so that one does not take him with the same seriousness as one does his work. In the final analysis, he is only the precondition of his work, its maternal womb, the soil, or in some cases, the dung and manure on which, out of which, it grows—and thus, in most cases, something that we must forget about, if we want to enjoy the work itself.” (Nietzsche, On the Genealogy of Morals, 3rd essay, Ch. 4 http://nw18.american.edu/~dfagel/genealogy3.htm)

As polemical as Nietzsche can be, his point about the relationship between the artist and his work is valid: the process of interpreting one’s art or action is a different one from producing it, precisely because living out or producing a great work of art, or action, does not necessitate understanding its cultural importance or significance. In fact, this would be tremendously difficult if not impossible while still living “in the moment” that such an event was created or occurred, without the context of the future to show its true place. This is what Nietzsche meant when he called the artist the “precondition”, “womb”, or “soil” of his work; that though the work is grown within and born from an artist or actor, it does not truly belong to him, nor was its form created by him, though he was the “soil” in which the product grew. For a preeminent description and further evidence of the existence of such a process, we must look to the first lines of Dante’s Inferno:

“In the middle of the journey of our life, I came to myself in a dark wood, for the straight way was lost. Ah, how hard a thing it is to say that wood was, so savage and harsh and strong that the thought of it renews my fear! It is so bitter that death is little more so! But to treat of the good that I found there, I will tell of the other things I saw.” (Dante, Inferno Canto I 1-7, Durling tr.)

Observe the passive imagery, “I will tell of the other things I saw,” and especially the fact that the pilgrim does not insist that he created his image, but rather that he simply perceived it and is not recollecting it for us. Dante’s narrative continues in that vein.

“I cannot really say how I entered there, so full of sleep was I at the point when I abandoned the true way.” (Ibid lns 10-12)

Again, Dante insists on unconscious and passive imagery: “I cannot really say how I entered there.”; “so full of sleep was I at the point when I abandoned the true way.” This is not the language of a conscious and discerning person actively choosing at each moment how to construct this myth. No, though the language may be his own, the experience was autonomous, or self-creating within him, and he was but the steward or “soil” who recorded and conveyed it by the page. In fact, if one simply turns to Canto II of Dante’s Inferno, one sees him explicitly agree with this fact by crediting the muses, or the unconscious, for the story he is to tell: “O muses, O high wit, now help me; O memory that wrote down what I saw, here will your nobility appear.” (Ibid Canto II lns. 7-9). Not only does Dante credit the imaginative or creative unconscious with bringing him to the place in the road where the story begins, but he even credits the muses, or the unconscious, with helping him find expression of the tale. Though, of course, he is consciously linking himself to Virgil and his Aeneid, it is just as clear that the story, its words, and its impact expressed itself through Dante.

Before concluding, let us briefly return to Campbell, and see whether he maintains himself in error:

“The metaphors by which they live, and through which they operate, have been brooded upon, searched, and discussed for centuries–even milleniums; they have served whole societies, furthermore, as the mainstays of thought and life. The culture patterns have been shaped to them. The youth have been educated, and the aged rendered wise, through the study, experience, and understanding of their effective initiatory forms. For they actually touch and bring into play the vital energies of the psyche[my italics].” (Joseph Campbell The Hero with a Thousand Faces P. 256-257)

Campbell has hit upon the utter value and power of myth: that it brings forth and springs from the vital and latent energies of the human spirit–that in accessing, living, and bringing forth a myth–a human essentially lives out his and his times’ vocation, for the myth is not consciously created so much as it is vitally lived or received. In this, Campbell is an enormous help to understanding the power, meaning, and proper function of myth. It is in the quote which follows which he unconsciously attempts to lead us astray.

“Until the most recent decades, [myths] were the support of all human life and the inspiration of philosophy, poetry, and the arts. Where the inherited symbols have been touched by Lao-tse, Buddha, Zoroaster, Christ, or Mohammed–employed by a consummate master of the spirit as a vehicle of the profoundest moral and metaphysical instruction–obviously we are in the presence rather of immense consciousness than of darkness.” (Ibid. P. 257)

Campbell’s error, as stated above, lies not in his perception of the function of myth nor in his choice of the “masters” through which myth is received. It is, however, his understanding that the consciousness of the recipient “adds to” or creates the myth rather than the fact that it is the receptivity of the master, or the consciousness, which allows the myth to speak through him. Therefore, it is not at all the size of one’s consciousness which makes one capable of living out a myth, but one’s receptivity which allows one’s self to be expanded by the transformational aspects of myth. So when Campbell says the following, we will understand him to be speculating in the service, perhaps, of his own personal attempt at a theory about myth rather than correctly expounding the facts about the creation of myth, which is our goal:

“And so, to grasp the full value of the mythological figures that have come down to us, we must understand that they are not only symptoms of the unconscious (as indeed are all human thoughts and acts) but also controlled and intended statements of certain spiritual principles [my italics], which have remained as constant throughout the course of human history as the form and nervous structure of the human physique itself.” (Ibid. P. 257)

Now, although Campbell is correct that myths exhibit, form, and are the result of “certain spiritual principles” and that many of the values, teachings, and characteristics of myths are constant throughout space and time, it is simply impermissible for him to say that these values and myths are “controlled and intended” statements as if the authors of them tailored and created the myths to fit the world. Such a thought is just as inflated and misguided as assuming that an athlete has created his own physique; though the athlete may slightly augment and improve what nature has given to him for his sport, he may not substantially alter or create for himself a new physical body suitable to his own needs. Such is the case with the authors above as well. Though they might slightly tailor and trim the myths to suit their time, style, and ability, they do not create, but rather receive, the material which they have presented in their various living myths.

In conclusion, Campbell will help us to see, without error this time, the ultimate source and purpose of myths:

“Briefly formulated, the universal doctrine teaches that all the visible structures of the world–all things and beings–are the effects of a ubiquitous power (the unconscious(my addition and italics) out of which they rise, which supports and fills them during the period of their manifestation, and back into which they must ultimately dissolve.” (Ibid. P. 257)

The ultimate well-spring of myth is the creative unconscious, and from it every myth arises which invigorates, unites, and informs a people. Though the expression may differ in word, action, or consequence, the ultimate source of every myth is the same. And in finding or receiving the myth which unifies and gives meaning to a person or people today, one need only, as Dante has written, “come to one’s self in a dark wood.”